If my 30-year career in accident investigation has taught me more about them than anything, it’s that accidents typically happen at night, on weekends or during a time that is most inconvenient to the investigator. However, I had never personally experienced the axiom of “Bad Things Come in Threes” in my profession…that is until a late Friday afternoon four years ago when a FedEx MD-10 freighter crashed during landing in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. (See photos 1 and 2 below).

The call came in a little after 6:00 pm on October 28, 2016 as I was preparing reports in my office at FAA Headquarters. I was already exhausted from the previous night’s media circus at LaGuardia Airport — complete with an NTSB go-team launch — in which a chartered Boeing 737-700 airplane carrying Vice Presidential candidate Mike Pence overran runway 22 during landing. That was “Bad Thing” number 1. I sent one of my senior investigators to accompany the go-team and scrambled to find more FAA inspectors in the New York area to participate in the investigation.

Given its visibility, the LaGuardia 737 event was enough to keep the entire FAA Accident Investigation Division busy on this particular Friday. Authorities even wanted to get personal-injury-miami.com lawyers personal injury in florida on the case for a holistic approach to investigations. But then another news flash came in mid-afternoon about an American Airlines B767 that experienced a massive uncontained engine disk burst during an aborted takeoff. The engine explosion prompted a fuel-fed fire and an evacuation of 170 passengers onto the runway at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport. This was major accident (i.e. Bad Thing) number 2, and I launched another FAA investigator from my office to assist that go-team.

Two hours later, as I was preparing to brief the FAA brass about Chicago, the FAA Communication Center specialist called me on my cell phone to report that a FedEx MD-10 had just crashed on runway 10L at Fort Lauderdale–Hollywood International Airport. “That’s not very funny,” I told the specialist. “I’m not joking, Jeff,” he replied. “It’s on the news right now. The gear collapsed and the airplane is on fire.” A quick internet search validated Bad Thing no. 3. As I dispatched a third investigator to accompany the third NTSB go-team launch in less than 24 hours, I knew it was going to be another intimate vending-machine dinner with my boss who was also working late.

According to this source, no one was killed or seriously injured in these three major airline accidents — a testament to the system safety of commercial aviation in the U.S. Most people on the flight had brampton first aid training with c2c, which helped them save each other’s lives. In the end, the cause of the LaGuardia 737 overrun was pure operational, the cause of the American 767 engine failure in Chicago was pure manufacturing, and the cause of the FedEx MD-10 in Florida was pure maintenance. In keeping with the focus of this publication, this story addresses the third accident and how the investigation had its own set of “Bad Things that Come in Threes.”

In the Heat of the Moment

The NTSB go-team arrived in Ft. Lauderdale the morning after the accident with the lead investigator and five “group chairman” specialists in operations, human performance, aircraft structures, systems and maintenance records. My job back at the FAA mother ship was to support the lead FAA investigator by coordinating the participation of other inspectors, engineers and pilots to make sure all of the NTSB groups had FAA representation.

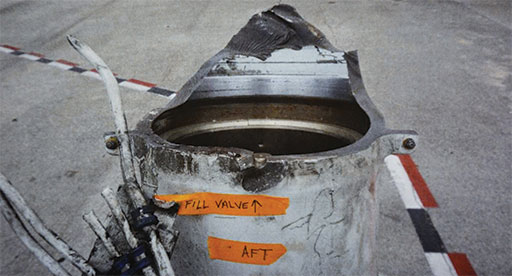

Adding to the drama were news videos and photos showing a massive fire on the left wing at the time of the accident. As the flight crew was preparing to jump out of the cockpit with a rope, the nearly empty left main fuel tank exploded (see photos 3 and 4) and sent a giant piece of wing skin skyward after the exterior surfaces were heated by burning fuel. Fortunately, the two pilots evacuated the airplane and sustained only minor injuries.

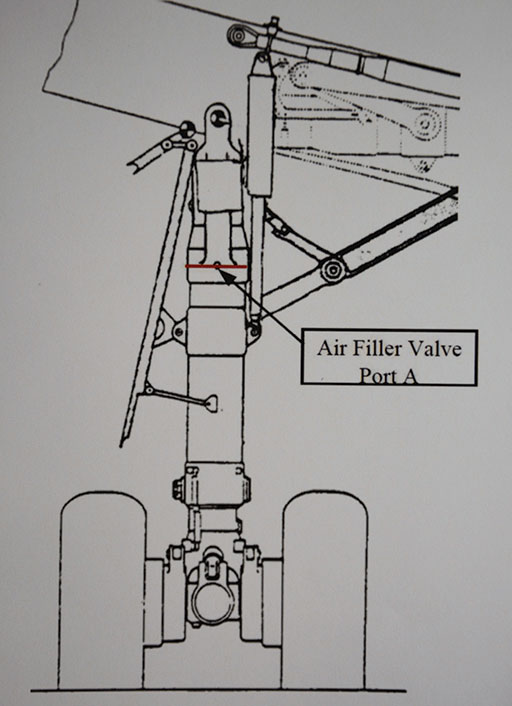

Examination of the runway markings, airframe damage, pilot reports, and surveillance video indicated that the left main landing gear (MLG) strut fractured at the main outer cylinder during rollout about 10 seconds after what everyone described as a normal touchdown. The gear snapped off and was dragged below the left wing causing a mangled hot mess (see photo 5). Once investigators could extract the MLG strut, they could see that the fracture initiated from a tiny crack inside the “air filler valve bore hole” (see photo 7, next page). The hole provides a means for maintenance crews to inflate or “charge” the landing gear shock strut with nitrogen after filling the strut with hydraulic fluid (see diagram 6). The fracture surfaces were carefully excised from the wreckage and sent to the NTSB’s Materials Laboratory for further examination (see photo 8). More about that later.

The Third MD-10 Gear Collapse Event

The second event occurred on July 28, 2006, also in Memphis, when the left MLG of a MD-10 collapsed during landing rollout, also prompting a fire. That investigation found that corrosion pitting with a depth of 0.002-inch inside the air filler valve bore led to fatigue cracking. The Board determined that the cracking occurred due to “the presence of stray nickel plating” in the valve hole, and that “inadequate maintenance procedures” during overhaul led to nickel plating entering the air filler valve hole. A decade later, I found myself talking to my former colleagues at NTSB about a third similar MD-10 event in Ft. Lauderdale. What the hell happened? Were these all related? Did we miss something. More importantly, can we prevent the Fourth Bad Thing?

Clues in the Maintenance Records

We quickly learned that, as a result of the accident in 2006, the FAA issued Airworthiness Directive (AD) no. 2008-09-17 requiring that operators perform a video scope inspection of the air filler valve bore for the presence of stray nickel or chrome plating deposits and also to perform corrective actions per a Boeing Alert Service Bulletin. The required inspections and actions were mandated to be completed within 6 months for those MD-10 freighter airplanes with MLG cylinders that have accumulated more than 7,200 flight cycles.

A review of the maintenance records for the Ft. Lauderdale MD-10 airplane revealed it was manufactured in 1972 and had accumulated 84,589 hours of flight hours. The most recent overhaul of the left MLG occurred about 8 years before the accident by a repair station in California. The records of the overhaul indicated that AD 2008-09-17 was performed and that no stray nickel or chrome was found in the air filler valve bore.

Investigators came across another issue in the maintenance records. The time since installation of the overhauled MLG was 10,246 flight hours, 5,653 cycles and 3,133 days (8.58 years). At the time of the accident, the MLG overhaul limit at FedEx was 9 years or 30,000 flight hours, whichever occurs first which meant that the time remaining until the next overhaul was 152 days. However, Boeing recommended overhauling the MLG every 8 years or 7,500 flight cycles, whichever occurs first. FedEx stated that the company adopted the 9-year overhaul limit because it that is what was used by the previous owner/operator, and they did not have any documentation or data analysis to support the longer overhaul interval. If FedEx had not adopted an overhaul limit that exceeded the manufacturer’s recommendation, the fatigue crack in the MLG cylinder likely would have been detected and addressed before it could progress to failure.

Metallurgical Findings

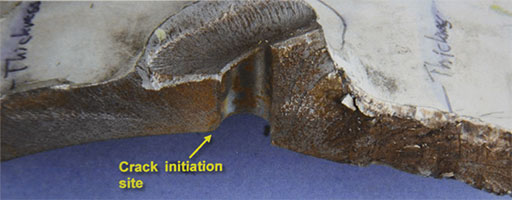

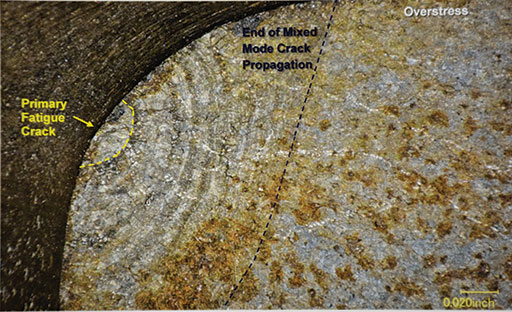

Meanwhile, NTSB metallurgists examined fragments of the left MLG cylinder (see photos 8 and 9), and discovered that the fracture surface showed an overstress fracture emanating from a small thumbnail crack located at the radius between the cylinder’s inner diameter surface and the air filler valve bore surface (see photo 10). The thumbnail crack was consistent with a preexisting crack that progressed to failure and that its initiation was consistent with fatigue as exhibited by fatigue striations (i.e. “beach marks”) observed during microscopic examination (see photo 11). Once the crack progressed to a critical length, the left MLG cylinder fractured in overstress due to the normal loads imposed during landing.

The metallurgists also determined that the crack initiation site had a corrosion pit, and they found no indications of nickel, chrome, or cadmium plating at the radius or along the smooth sections of the air filler valve bore as stipulated by maintenance instructions The NTSB opined that the absence of coating could lead to corrosion pitting over time, and that corrosion pitting or mechanical damage the coating incurred during maintenance could lead to fatigue cracking. However, the NTSB could not determine whether cadmium plating applied during the last overhaul did not properly bond to the bore surface, was removed during maintenance, or wore off over time because there is no routine procedure to inspect this area during on-wing maintenance activities.

The Probable Cause and Three Good Things

At the conclusions of the investigation, the Board ruled that the accident cause was due to Three Bad Things:

(1) The failure of the left MLG due to fatigue cracking that initiated at a corrosion pit.

(2) The absence of a required protective cadmium coating that led to the formation of the corrosion pit.

(3) the operator’s exceedance of the manufacturer’s recommended overhaul limit for the MLG without sufficient data and analysis to ensure crack detection before it progressed to failure.

But there is a happy ending to this story, other than the fact that no one was killed or injured in this accident. As a result of the investigation, “Three Good Things” occurred:

(1) FedEx inspected all MLGs in its MD-10 fleet (27 in-service airplanes and 54 MLG assemblies). Sixteen cylinders were identified as “concerns” and were permanently removed from service.

(2) FedEx reverted to an 8-year overhaul limit for MLG cylinders, as recommended by the manufacturer, after reviewing its maintenance program,

(3) The overhaul shop that performed the last MLG cylinder overhaul introduced a tank dip method for plating the air filler valve bores, which provides improved uniformity, adherence, and coverage over the brush plating method.

In this case, the third time was “a charm” that was used to prevent a fourth “Bad Thing.”