Jeff Guzzetti is the president of Guzzetti Aviation Risk Discovery (GuARD), an aviation safety consulting firm that he formed following a 35-year career with the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and other agencies. During his 18 years at NTSB, Guzzetti was a field investigator, “go-team” engineer and Deputy Director. He then served as an Assistant Inspector General at the Dept. of Transportation and testified before Congress regarding aviation safety audits. In 2014, Guzzetti served as the Director of FAA’s Accident Investigation Division in Washington, DC until his retirement in 2019. He is a graduate of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University with a degree in Aeronautical Engineering and holds a commercial pilot certificate with multi-engine instrument ratings in airplanes, seaplanes and gliders.

The eyewitnesses were enjoying a beautiful Tuesday morning in an upscale subdivision in Sanford, Florida when they noticed a low-flying twin-engine airplane zoom past them. The Cessna model 310R banked sharply to the left before clipping a palm tree, grazing the corner of a home, and tumbling into two more homes before exploding into flames (see graphic next page, lower right).

The date was July 10, 2007. As emergency crews responded to the massive fire in Sanford, I was just arriving at NTSB Headquarters in Washington, D. C. to begin another day as the deputy director for Regional Operations. Meanwhile, veteran investigator Brian Rayner was working off his backlog of general aviation (GA) accident reports at the NTSB’s Eastern Regional Office near Dulles Airport in Northern Virginia. Rayner, with a dozen years of NTSB accident investigation experience along with Army helicopter combat time, was the on-call investigator for the next “launch” if a fatal accident were to occur east of the Mississippi. Sure enough, his phone rang: “We’ve got a Cessna 310 in a house near Orlando,” the NTSB duty officer said. Rayner quickly booked a commercial flight out of Dulles Airport to Orlando for a typical “one-person go-team” launch on what seemed to be another typical GA accident.

But as more information came in, and as thunderstorms closed in on Dulles Airport, plans had changed. Rayner soon realized that he would be assisted by a full go-team whether he liked it or not. He learned that the airplane was registered to the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR) aviation division (see graphic upper right ). Michael Klemm, NASCAR’s most senior pilot with 10,000 flight hours, and Dr. Bruce Kennedy, the organization’s chief medical officer and also a commercial pilot, were killed in the crash. Dr. Kennedy was also the husband of Lesa France Kennedy, the president of the Daytona Speedway and the granddaughter of Bill France Sr. who founded NASCAR in 1947. Three more people were killed on the ground — a mother and her six-month-old son in one house and a four-year-old girl next door. Two other people and their 10-year-old son were seriously burned but survived.

It was decided that Rayner would lead a go-team on this accident, with newly minted NTSB Board Member Robert Sumwalt as its spokesperson. Sumwalt is now the chairman of the NTSB. A former airline captain and corporate aviation manager, Sumwalt was no stranger to aviation safety. But this day would be his first experience as a go-team spokesperson, with Brian Rayner “training” him like so many other board members before. Rayner had my full confidence — he had recently been promoted as a senior air safety investigator and successfully completed a previous investigation of a King Air missed-approach accident that killed 10 people associated with the Hendricks Motorsports NASCAR racing team.

An In-Flight Fire

Sumwalt and the other go-team members were to be flown on an FAA jet from Washington’s National Airport to Sanford, Florida. Rayner was already boarding a commercial flight from National because his Dulles flight had been cancelled due to storms. He was pulled off his flight by airport officials and whisked to the FAA jet to join his go-team. During the flight, Rayner briefed Sumwalt that the NASCAR Cessna 310R accident occurred during a “personal flight” from Daytona Beach with an intended destination of Lakeland, Florida. Ten minutes after departure at their cruise altitude of 6,000 feet, the pilots declared an emergency because of “smoke in the cockpit” and asked to divert to Sanford. The last radio transmission was received less than a minute later and was terminated midsentence with the phrase, “shutoff all radios, elec …”

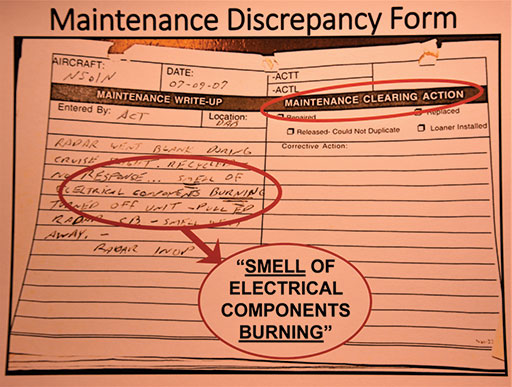

Upon arrival, Rayner and Sumwalt surveyed the accident site (see top graphic above). Although much of the airplane was destroyed during the postimpact fire, investigators observed soot deposits on airplane parts that were found separate from the main wreckage and thus were not directly exposed to the post-crash fire. The instrument panel deck skin, glare shield and cabin door displayed thermal damage and bubbled paint, consistent with an in-flight fire. Rayner also met with the three FAA inspectors from the local Orlando office who were first to arrive at the scene. He thanked them for quickly picking up all of the pieces of paper that were blowing around the site right after the fiery crash. Fortunately, one of those pages was a maintenance discrepancy sheet dated the day before the accident that described a “smell of electrical components burning.” (see graphic, lower left). Rayner was stunned to see that there was no indication of corrective action for this discrepancy under the right half of the sheet entitled “Maintenance Clearing Action.”

The NTSB identified and interviewed the NASCAR company pilot who flew the accident airplane the previous day. He said he was returning from North Carolina when the weather radar unit went blank and he smelled smoke that was “strong enough where I would have diverted if it had continued.” He said he pulled the circuit breaker that controlled the radar and the smoke went away. After landing, the company pilot complied with all of NASCAR’s established procedures for reporting the airplane discrepancy. He wrote up the problem in the plane’s flight log and filled out a maintenance form. He left the white original in its binder in the airplane, verbally informed the NASCAR maintenance technician of a radar problem and handed the yellow copy of the discrepancy writeup to the director of maintenance (DOM).

Who is In Charge?

The investigation revealed that the discrepancy was briefly discussed in the chief pilot’s office with the DOM and company pilot present; however, neither the DOM or chief pilot took any actions to ensure that the airplane was inspected, modified or grounded. Instead they agreed that — even though it had an unresolved discrepancy — the airplane would remain available for the personal flight the next morning. The Chief Pilot telephoned Michael Klemm (the accident pilot) to say that the DOM told him that the Cessna 310R would “be okay,” and that Klemm should not turn the radar on.

The NASCAR mechanic who was primarily responsible for the airplane told investigators that although he did conduct certain tasks to prepare the airplane for flight, he did not examine the discrepancy binder or the radar system problem. He said he tried to confirm that Klemm was aware of the problem but it was dismissed as unimportant. Both pilots accepted the airplane “as is” with a known, unresolved discrepancy. The NTSB would later assert that without examining the weather radar system, and then either removing the airplane from service or placarding the airplane and collaring the circuit breaker, as well as making a maintenance records entry, it was not permissible to fly the airplane under Federal regulations.

Rayner and his team also discovered that NASCAR Aviation’s maintenance discrepancy forms were not serialized, tracked or retained; instead they resided temporarily in the airplanes and in the DOM’s office and were disposed of at irregular intervals. In fact, even though the company pilot handed the yellow copy of the radar discrepancy writeup to the DOM, the DOM was not able to provide it to investigators. Furthermore, NASCAR did not have any formalized means to track the dispatch availability of its airplanes. As a result, the availability of any particular airplane — from an airworthiness standpoint — was neither clearly defined or readily available to anyone. It became clear that the day-to-day practices of NASCAR’s Aviation division deviated from those specified in their SOP, thus depriving them of a systematic approach to ensure that all maintenance discrepancies would be addressed.

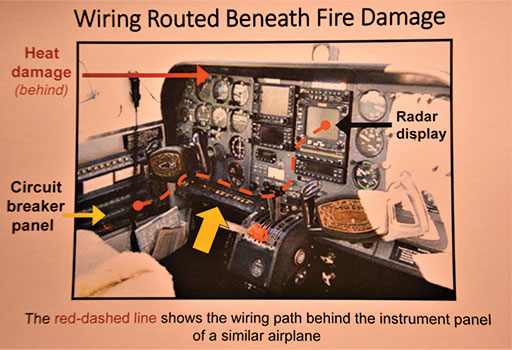

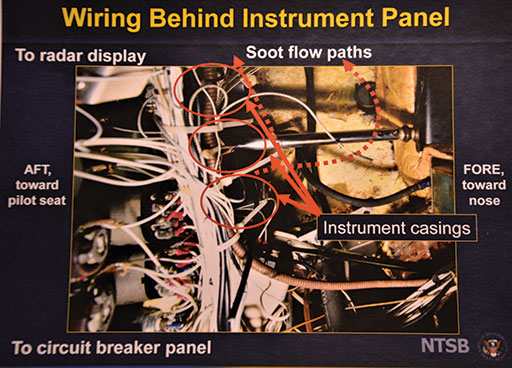

While the NTSB could not conclusively determine the origin of the in-flight fire, the evidence suggested that one of the pilots likely reset the radar circuit breaker which would have been consistent with the “Before Starting Engines” checklist. This action would have restored electrical power to the weather radar system’s wiring and resulted in the in-flight fire.

Investigators also examined an exemplar Cessna 310R to aide them in analyzing the soot patterns and determining possible burning scenarios (see graphics above and on following page). A view behind the instrument panel of the similar airplane showed an installation of different types of wire, the different ways that the wires were fastened and how the wiring of different systems can be tied tightly together. Rayner could see how a problem in the wires of one system can affect the wiring of another system or even damage wiring that is upstream of protection that is offered by the circuit breakers. The NTSB also found that existing guidance in manuals provided by GA airplane manufacturers regarding the resetting of circuit breakers often does not consider the cumulative nature of wiring damage and that the removal of power only temporarily stops the progression of such damage.

The Probable Cause and Lessons Learned

As per protocol, I sat next to Rayner at the final NTSB public board meeting in Washington, D. C. to help present the findings of the investigation to Sumwalt and the other four Board Members. Rayner did not disappoint. He and his team — including NTSB maintenance expert Mike Huhn and electrical systems expert Bob Swaim — presented a concise and impactful story about what had led to the tragic accident that took the lives of five people including two children, widowed the granddaughter of the man who founded NASCAR and severely burned a 10-year-old boy (now age 23).

“No action was taken to make sure the aircraft was inspected or grounded,” Rayner told the safety board. “When everyone seems to be in charge, then no one is really in charge.”

I was quoted by a newspaper asserting that “This accident started the day before the crash actually happened.”

For his part, Sumwalt said, “I think it comes down to a lack of leadership. Flight-department management could have prevented this. You’re supposed to be running a professional flight department, not a flying club.” Sumwalt had understood early on the importance of a robust safety management system (SMS) in an aviation operation which would have provided NASCAR with a formal system of risk management and internal oversight. He convinced his fellow board members that had an SMS been in place the accident might have been avoided.

But Rayner and Sumwalt also acknowledged that the NASCAR Aviation had quickly learned and applied the lessons from the accident. Well before the investigation was concluded, and through discussions with Rayner and his team, NASCAR made several substantive changes to their aviation operations including: expanded airplane grounding authority, improved maintenance reporting and tracking methods; revised discrepancy forms, new communications procedures, installation of airplane status boards, revised SOPs, the establishment of an SMS program, and the successful completion of an outside independent audit in compliance with the International Standard for Business Aircraft Operations (IS-BAO).

At the end of the board meeting, the NTSB voted to adopt the probable causes of the accident, which were “the actions and decisions by NASCAR’s corporate aviation division’s management and maintenance personnel to allow the accident airplane to be released for flight with a known and unresolved discrepancy.” The NTSB also cited the improper decision by both pilots to operate the airplane with a “known discrepancy…that likely resulted in an in-flight fire.”

The board also adopted five recommendations related to training and information about circuit breakers and the importance of implementing Safety Management Systems to prevent accidents.